The Message of the Magi

The Magi, (or as they are more commonly known, the Wise Men) are mentioned only once in the whole Bible. Their brief story is found in the first 12 verses of the 2nd chapter of Matthew’s gospel…

1After Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, during the time of King Herod, Magi from the east came to Jerusalem 2 and asked, “Where is the one who has been born king of the Jews? We saw his star in the east and have come to worship him.â€

3 When King Herod heard this he was disturbed, and all Jerusalem with him. 4 When he had called together all the people’s chief priests and teachers of the law, he asked them where the Messiah was to be born. 5 “In Bethlehem in Judea,†they replied, “for this is what the prophet has written: 6 “‘But you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for out of you will come a ruler who will be the shepherd of my people Israel.’â€

7 Then Herod called the Magi secretly and found out from them the exact time the star had appeared. 8 He sent them to Bethlehem and said, “Go and make a careful search for the child. As soon as you find him, report to me, so that I too may go and worship him.â€

9 After they had heard the king, they went on their way, and the star they had seen in the east went ahead of them until it stopped over the place where the child was. 10 When they saw the star, they were overjoyed. 11 On coming to the house, they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshiped him. Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold and of incense and of myrrh. 12 And having been warned in a dream not to go back to Herod, they returned to their country by another route.

Despite this story being quite short, the Wise Men have become a staple part of the Christmas nativity scene, inspiring one of my favourite Christmas carols, “We Three Kings”. Sadly however, this carol is a perfect example of how we so easily re-shape Christmas into something that suits our fairy tale version of the Bible, rather than reading and responding to what the gospel record actually says. Here are just a few ways we get the story of the Magi completely wrong:

MISTAKE #1: They weren’t kings.

The Magi are never referred to as kings. The concept of kings coming to see Jesus and pay homage is one that makes a wonderfully powerful statement about the authority of Christ over all human rulers. It just has no basis in the original story. I have even heard it said that God ensured that both the poor (represented by the shepherds) and the rich (represented by the “kings”) were present so that we knew that Jesus came for people of every demographic. But no, the Magi were not royalty. They weren’t even necessarily wise (To me, “Wise Men” gives them a sort of ancient guru-like feel). All the text tells us about the Magi is that they came from the East. That doesn’t even tell us much. Were they Magi from the far, far east? Were they gentiles? Were they Jews? Who knows? Read the text above again. Remember, that’s all we really have to go on.

Now, the term “Magi” is mentioned in several other cultures. Some Ancient Greek sources refer to a specific tribe of people  in Ancient Iran (then known as Media), but it also is used as a generic word for any sacred sect or mystical order. This is how we get the generic word “magician” (a “magi” person). Ancient Persian sources refer to the Magi being the religious sect that Zoroaster was born into, and some time before 6 BC, in the eastern parts of Ancient Iran, his teachings became the foundation of the religion, Zoroastrianism, also known as “Magianism”. This religion was alive and kicking at the time that the biblical story is set and this has led some to argue that the Magi were Zoroastrians (or at least converts from Zoroastrianism). If that is true, then they were just some religious guys who were seeking the Jewish Messiah. Now, I don’t want to downplay that. In fact we shouldn’t downplay that. It’s awesome! There’s no need to stretch the story to make them kings or even particularly wise (other than the wisdom they showed in seeking Jesus, but then we should equally call the shepherds “wise men”!)

MISTAKE #2:Â There weren’t only three.Â

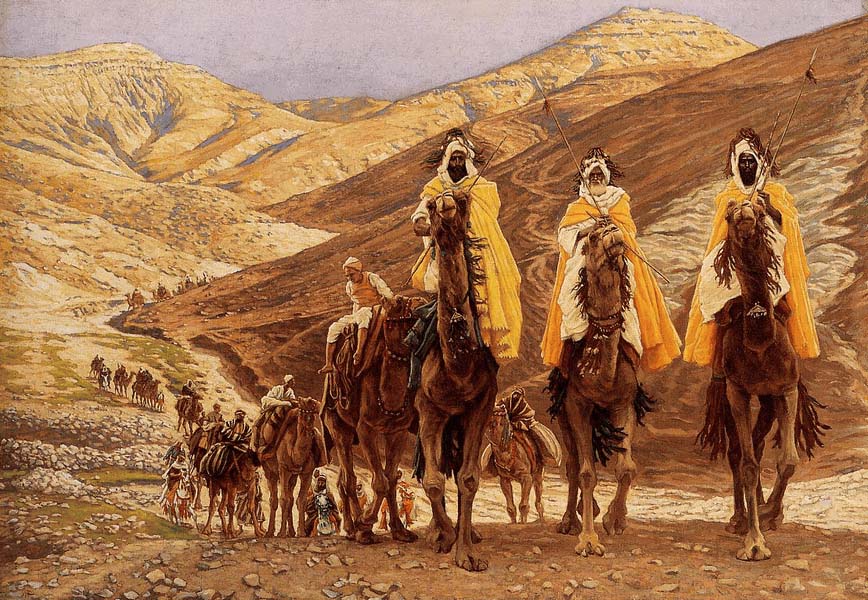

All the pictures, movies, nativity sets and carols about “We Three Kings”, suggest that the Magi were a small band of men riding camels, making a lonely trek across the sand dunes and joining the quiet and solemn scene, almost just slipping in at the back unnoticed. Over the year’s we’ve even invented names for them – Melchior, Caspar and Balthazar. But read the story again and you’ll find the only reference to the number three is the fact that they brought three different types of gifts (“Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold and of incense and of myrrh.”  Matthew 2:11). Also, the implication from the text is that it wasn’t just three gifts, but multiple amounts of gold and incense and myrrh as it was taken from their “treasures”.

The biggest clue that the Magi included more than three men, is found in the first 3 verses of the story. Verses 1 and 2 describe the Magi arriving at Jerusalem and asking where the Messiah was. If they were three religious men on camels, this arrival wouldn’t have made anyone take notice. Jerusalem was a huge city and it had a constant traffic of visitors from a variety of nations. But when the Magi arrive, what do we read in verse 3? “When King Herod heard this he was disturbed, and all Jerusalem with him.”Â

The arrival of the Magi caused a disturbance across all Jerusalem which even reached King Herod himself, enough to make him fearful of losing his own royal position. How many people must have been part of the Magi’s procession for their arrival to have such an epic impact? It sounds more like there could have been hundreds of Magi! There could have been a massive pilgrimage of seekers with horses and elephants and musicians and an entourage of servants carrying loads of treasures for “the one who has been born king of the Jews“! Who knows? There is absolutely no description of the number of Magi who had come from the east or what their group was like. The only thing that can guide us, is the disturbing effect they had on the great city of Jerusalem and the security of Herod the King. Does that sound like three guys? Not likely.

MISTAKE #3:Â They weren’t even at the Nativity scene.Â

That’s right! Every children’s Christmas pageant and that beloved family Nativity set that sits on your mantlepiece has got it wrong! The Magi were not there alongside the shepherds and the cattle by the manger. They weren’t even present at the event of the first Christmas! They came along possibly years later, after Jesus and Mary have moved out of the temporary emergency maternity ward mentioned in Luke 2:7 and moved into a house somewhere in Bethlehem (possibly staying with relatives, as Joseph had to go to Bethlehem for the census due to his family line. See Luke 2:4).

You can read where the Magi actually visited the child in Matthew 2:11-12: “On coming to the house, they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshiped him. Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold and of incense and of myrrh. And having been warned in a dream not to go back to Herod, they returned to their country by another route.” It clearly states that they came to a house, not the barn, stable or cave mentioned in Luke 2:7.

But is that the only reason why I think they were not there at Christmas? Not at all. The biggest clue is not emphatic, but it does make sense. This is the next part of the story found in Matthew 2:13-16…

13 When they [the Magi] had gone, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream. “Get up,†he said, “take the child and his mother and escape to Egypt. Stay there until I tell you, for Herod is going to search for the child to kill him.â€Â 14 So he got up, took the child and his mother during the night and left for Egypt, 15 where he stayed until the death of Herod. And so was fulfilled what the Lord had said through the prophet: “Out of Egypt I called my son.â€Â 16 When Herod realized that he had been outwitted by the Magi, he was furious, and he gave orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years old and under, in accordance with the time he had learned from the Magi.

Okay, if you’re getting confused, this is how the story of the Magi has gone: Around the time Jesus is born the Magi see a star appear and they somehow get the idea that this signifies that the Jewish Messiah has been born. The story doesn’t elaborate on how they learned this, but they at some point decide to make the journey from where they live to Jerusalem. When they eventually get to Jerusalem, they meet with King Herod who asks them exactly when they first saw the star. They then leave, following the star to the house where Mary, Joseph and Jesus are now living. They respond to Jesus as a king – bowing down to him, worshipping him, and paying homage to him with their treasures.

Now, they were supposed to report back to King Herod, but God warns them to go back to their home in the east without telling the King anything. The King is furious because he wanted to know exactly where Jesus is living so he can find him and kill him. He only knows two things: 1. Where Jesus is approximately (somewhere in or around Bethlehem), and 2. How old Jesus is approximately at this stage.

He works out Jesus’ age by how long it’s been since the star originally appeared (marking when Jesus was born). We aren’t told exactly when this is, but we are told that Herod orders the death of all the children in and around Bethlehem ages two years old and under. This means that Jesus is not a new born any more. In fact, Jesus could be up to two years old according to King Herod’s logic. Maybe Jesus was only one year old and King Herod ruthlessly wanted to just make sure that he got Jesus by killing children older than he needed to, just in case.

Now, this horrible story, traditionally entitled, “The Massacre of the Innocents” really deserves its own contemplation (my brother wrote a thoughtful blog on it which you can read here), but for the purpose of this blog, it points out that the whole story of the Magi and the star is not set at Christmas at all. Jesus is not a newborn baby lying in a manger when the Magi follow visit, he’s a one or two year old child and they visit Jesus at the house he is living in.

But so what? What’s the problem with tweaking the stories of the Bible so that they fit better into carols and nativity sets? Who cares if the Magi actually aren’t a part of Christmas? Who cares if the “We 3 Kings” were actually “We 300 Zoroastrians”?

Well, I think that’s the problem. We don’t care to read what the Bible actually says. Like in the video above, spoken by the Mayor of Orlando, we are happy to “celebrate the biblical story of the three kings”, without really caring if such a “biblical” story even exists. Although it’s still positive and a quasi-endorsement of the Bible, it’s actually promoting a way of changing the Bible to suit ourselves, rather than grappling the Bible as it stands to let it change us.

The best analogy I can think of to explain why this is an issue, is the Quentin Tarantino movie, “Inglourious Basterds”. You may not have seen the movie, but it’s sort of a fantasy re-telling of the events of World War 2, where a group of US soldiers plan to assassinate Hitler – and they succeed! Now, if you know you history, Hitler wasn’t assassinated by American soldiers, he committed suicide. Of course, one of the things that makes the movie, “Inglourious Basterds” such a clever movie is that this fact is known and so Tarantino can make this film as a sort  of “wouldn’t it have been cool if” sort of movie.

The best analogy I can think of to explain why this is an issue, is the Quentin Tarantino movie, “Inglourious Basterds”. You may not have seen the movie, but it’s sort of a fantasy re-telling of the events of World War 2, where a group of US soldiers plan to assassinate Hitler – and they succeed! Now, if you know you history, Hitler wasn’t assassinated by American soldiers, he committed suicide. Of course, one of the things that makes the movie, “Inglourious Basterds” such a clever movie is that this fact is known and so Tarantino can make this film as a sort  of “wouldn’t it have been cool if” sort of movie.

But imagine if that movie became the staple history of World War 2? What if all other historical records were ignored and that’s just how the Mayor of Orlando referred to the death of Hitler? What if sermons and songs were written about this fictional history, teaching us about the might of American soldiers and how they were even able to kill Hitler! Not only would this be a lie about America, it would also be an insult to the German resistance, who actually came the closest to assassinating Hitler on the 20th July 1944 with “Operation Valkyrie”. This is actually something I think Quentin Tarantino would hate to have happen, as the power of the fantasy of his film relies on the backdrop of the truthful history being known.

Likewise, when a false version of the Bible is told and re-enforced, it promotes the Bible, not as history, but as mythology and fairy tale. But I believe, more than any other religion, Christianity proclaims the Bible (and especially the gospels) as a record of actual, historical events that are real and true and have effected the history of the world. As Peter, the close friend and follower of Jesus wrote, “We did not follow cleverly invented stories when we told you about the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we were eyewitnesses of his majesty.” (2 Peter 1:16)

The message of the Magi is one of non-Jews (like most of the people reading this blog) seeking the promised Jewish Messiah. Their message is to bow down and worship Jesus like they did. It is a message worth listening to and following.

But the message of the Magi is also that if we are to really grapple with who Jesus really is and respond to him as he truly is – rather than how we would like him to be – we must not simply listen to the carols and the Christmas Day TV special. We must go back to the source material. Read the Bible for yourself! Don’t trust what I say about it in these blogs. Pick it up and read the actual words that are on the page. It’s hard to throw out the baggage and the expectations you may have about Jesus, but I encourage you to try to do so.

But the message of the Magi is also that if we are to really grapple with who Jesus really is and respond to him as he truly is – rather than how we would like him to be – we must not simply listen to the carols and the Christmas Day TV special. We must go back to the source material. Read the Bible for yourself! Don’t trust what I say about it in these blogs. Pick it up and read the actual words that are on the page. It’s hard to throw out the baggage and the expectations you may have about Jesus, but I encourage you to try to do so.

If in the end, you choose to follow Jesus, I want you to follow the real Jesus.

If in the end, you choose to reject Jesus, I want you to reject the real Jesus.

Because in the end, you’ll be standing before the real Jesus, and I’d hate for you to get a shock.

To leave you on a lighter note, I’ll finish this will my all-time favourite example of how we like to design our own Jesus. This scene is from the pretty lame movie, “Talladega Nights”, but it includes a very relevant line for this discussion, especially at this time of year. Will Ferrel’s character, Ricky Bobby says, “I like the Christmas Jesus best, and I’m saying grace. When you say grace you can say it to grown up Jesus or teenager Jesus or bearded Jesus or whoever you want.”

Enjoy and have a wonderful Christmas!

(7162)